When it comes to predicting how much sea levels will rise as global temperatures warm, the fate of Antarctica looms all-important.

The hulking mass at the bottom of the Earth is home to the world’s largest land ice reservoir. If Antarctica’s entire ice sheet were to melt, it could raise sea levels by nearly 190 feet, more than 9 times as much as Greenland could potentially contribute.

The world’s other glaciers and ice sheets contain more than enough water to cause major problems for coastal cities.

But scientists say that the Antarctic ice sheet is what stands between coastlines that resemble what we see today, and – if it collapses – a world map unrecognizable from the one we’ve known.

Still, the question of how much Antarctica will melt if humans keep heating up the planet – and how fast – is a major source of uncertainty when it comes to predicting sea level rise and the threat facing the roughly 600 million people currently living in coastal areas across the globe.

Two new studies published in the same scientific journal Wednesday agree on a lot – that ice melt globally from human-caused warming is a threat to coastlines around the world, and that planning needs to begin now for a future where sea levels are higher than they are today.

But they come to different conclusions about how Antarctica’s ice sheet might fare in a warming world.

One finds that there is no clear signal that Antarctica’s melting would necessarily increase or decrease under different global warming scenarios.

The other shows that Antarctica’s melt could accelerate drastically if the planet warms by 3 degrees Celsius, as it is currently on track to do later this century based on our current greenhouse gas emissions trajectory.

However, there is agreement that limiting global warming to 1.5 or 2 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels is vital to reducing the amount of sea level rise to which the world will have to adapt.

The 1.5-degree warming threshold is key to limiting sea level rise

One of two studies published in the scientific journal Nature is a complex and comprehensive modeling assessment that projects future melting across all of the world’s major land ice regions, from Antarctica and Greenland to the glaciers of the Himalayas, Alaska and elsewhere. The study involved 84 researchers based in 15 countries, and examined how much each of these sources could contribute to sea level rise under a host of different global warming scenarios.

Sea levels are expected to continue to rise this century, the scientists say, but how much depends on the scale and pace of human actions to limit global warming.

The researchers found that limiting warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius could cut expected sea level rise contributions from land ice globally to just over 5 inches by 2100. That’s roughly half what the report says we could expect to see if the world stays on its current emissions trajectory.

“That means that coastal flooding will still increase, but less severely if we manage to limit warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius,” said Tamsin Edwards, a climate scientist at King’s College London and a lead author of the study.

This potential reduction in melting is unlikely to be spread evenly across the major land ice sources, the authors found. Greenland’s ice losses, for example, would plummet by 70% if humans manage to hold warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius, while glacial ice losses elsewhere would fall less significantly, by roughly 50%.

The researchers reached a different conclusion on Antarctica. The study says that Antarctica’s ice sheet shows little variation in the amount it will contribute to sea level rise, even under scenarios where global temperatures climb above 1.5 degrees Celsius.

The study found that disintegration at the edges of the ice sheet and melting on its surface will likely continue, but that some simulations show that those losses could be offset by gains in snow accumulation on the continent.

“In Antarctica, it is very complex because a warmer world could mean more snowfall throughout the entire year, but it could also mean more melt at the side of the ice sheet where the ice shelf that’s floating over the sea can break up,” said Sophie Nowicki, a scientist and professor at the University of Buffalo and one of the lead authors of the land ice modeling study.

“You have those two competing effects of possible growth from snowfall and melt that’s resulting in the ice sheet thinning.”

The authors do say there is a chance that a more “pessimistic” scenario for Antarctica could come to pass: The study finds that that there is a 5% chance that sea level rise from land ice melt could exceed 22 inches by 2100, even if global warming is held to 1.5 degrees Celsius, with Antarctica playing a large role in driving that increase.

Sea level rise of that magnitude would spell disaster for many of the world’s coastal cities. The authors say that policy makers charged with protecting critical infrastructure should consider this large uncertainty about how Antarctica’s ice will behave in their plans for the future.

“If you own a nuclear power plant on the coast or if you’re defending London or New York, then you you might have the concern and the budget to protect against a higher level of risk,” Edwards said.

An alternate view of Antarctica’s future

The other study, also published in Nature, finds Antarctica’s ice is likely more sensitive to a rise in temperatures, especially an increase of above 2 degrees Celsius.

Under a scenario where global warming is limited to 2 degrees Celsius or less, the authors project that Antarctica’s melt could add just 3 additional inches to global sea levels by 2100.

But if global temperatures climb to 3 degrees Celsius, Antarctica’s contribution could nearly double to add 6 additional inches to sea levels by 2100. The study finds that Antarctic melt could pose an even larger threat in a 3 degree Celsius world, with a 10% chance that it could add nearly 13 inches to sea levels by the end of the century.

Rob DeConto, a climate scientist and glaciologist at the University of Massachusetts-Amherst and a lead author of this study, says that a tipping point for Antarctica’s ice sheet likely exists somewhere in between 2 and 3 degrees Celsius of warming, but exactly where is difficult to pinpoint.

“We don’t know exactly where it is,” Deconto said. “I’d like to hope that we’re wrong and it’s somewhere well above 3 degrees (Celsius).”

The scientists say that the differing projections offered by the two studies are owed in part to a process known as marine ice cliff instability (MICI), which suggests that massive ice cliffs at the edge of Antarctica could collapse rapidly into the ocean when weakened by warmer temperatures.

The researchers behind the first land ice study did not factor MICI into their modeling, while Deconto’s study did.

“It’s not in the other study, and we consider it kind of the key wild card in all of this,” Deconto said. “And it’s the reason why there’s a contrast between the findings of the two studies.”

A 2019 study authored by some of the same scientists behind the land ice study also questioned whether MICI would play a large role in driving ice loss in Antarctica in the future.

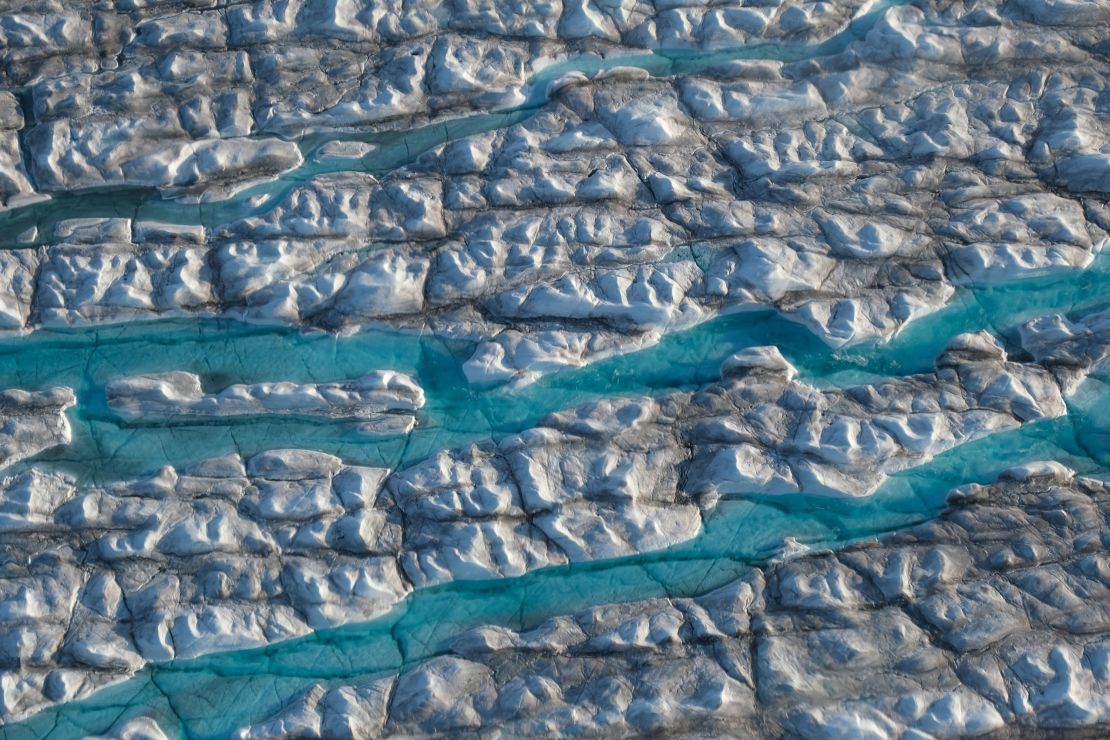

But recent evidence shows that sea level rise is already accelerating and increased melting in Antarctica is a major reason why.

Rates of sea level rise have more than doubled from 0.06 inches per year observed through most of the 20th century to 0.14 inches per year from 2006-2015.

And in a special report published in 2019, the UN’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change found that Antarctica’s ice loss tripled between 2007 and 2016 compared to the previous 10 years.

Since 1880, global sea levels have risen by an average of around 8 to 9 inches.

Melting land ice is responsible for about half of the sea level rise the world has experienced since 1993.

The other half is owed to “thermal expansion” in the world’s oceans, a process where water increases in volume as it heats up. And the world’s oceans have gotten a lot hotter due to human emissions of greenhouse gases – A study published last year found that the oceans are absorbing five Hiroshima-sized bombs worth of heat energy every second.

Despite the uncertainty over what will happen to Antarctica and differences in the studies’ findings, DeConto says that the key takeaway remains the same: Coastal communities need to prepare for a future where sea levels are likely higher than they are today.

“I think a common message between our studies is that we need to have flexible adaptation measures in place to deal with a wide range of possible sea level outcomes,” DeConto said.