President John Fitzgerald Kennedy was having a rough time of it in April 1961.

In office for less than three months, Kennedy was facing down what he and his advisers suspected to be an untrustworthy Central Intelligence Agency.

He would confirm his suspicion toward the end of the month, when Cuban rebels bankrolled by the agency invaded their Communist-held homeland. At a meeting with Secretary of State Dean Rusk and others on April 12, Kennedy had stressed he wanted the invasion to be a Cuban operation as much as possible, and the CIA assured him that the rebels were up to the job.

The result, a week later, was the Bay of Pigs fiasco, a military and political disaster that would only embolden Fidel Castro and his chief benefactor, the Soviet Union.

Kennedy blamed the Soviets for his bad April. In his inaugural address in January, he made an overture to Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev, inviting the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics to join the United States in “exploring the stars.”

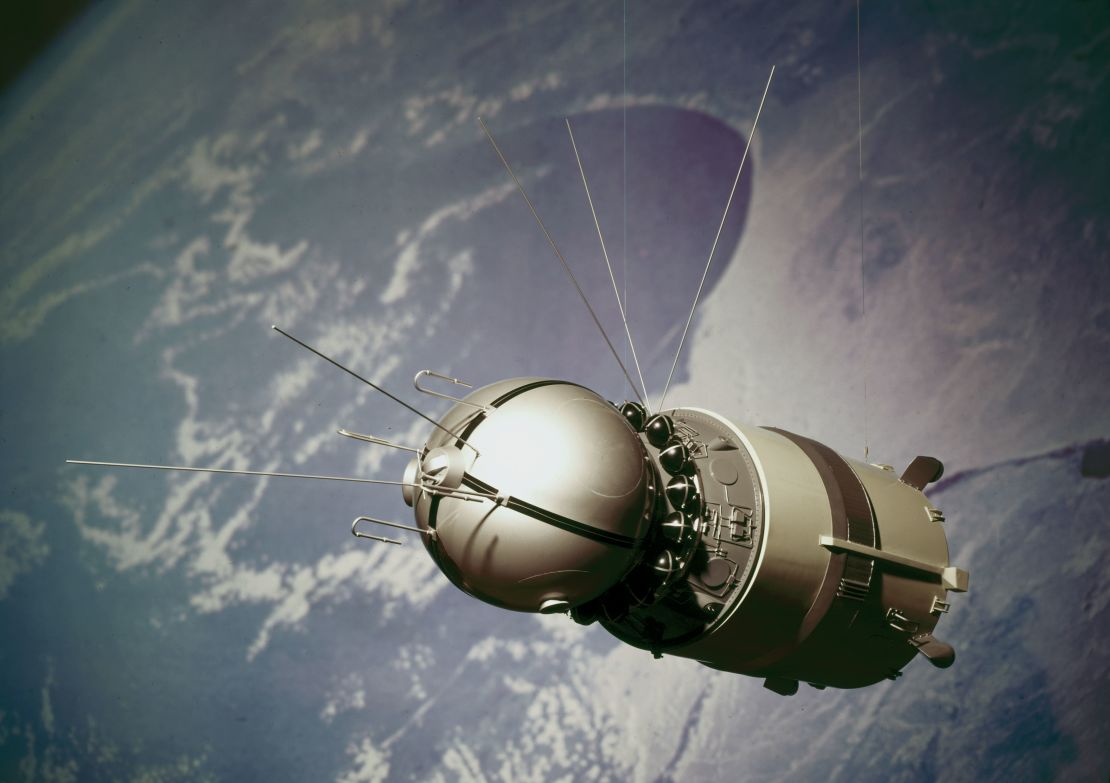

Khrushchev’s answer came 60 years ago, on April 12, 1961, when Soviet cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin circled the Earth aboard a spacecraft called Vostok 1. After parachuting from the craft near the Russian village of Smelovka, Gagarin landed a hero — and a major embarrassment for the United States, already stung by the Soviet first-in-the-race launch of the Sputnik 1 satellite four years earlier.

READ MORE: Famous firsts in space

The Vostok rocket was the brainchild of Soviet engineer Sergei Pavlovich Korolev. Embarrassed in turn by their failure to develop an atomic bomb before the Americans did, the Soviet leadership had poured a huge portion of the country’s budget into scientific research, building a testing ground and rocket base in Kazakhstan that, wrote Stephen Walker in his new book “Beyond: The Astonishing Story of the First Human to Leave Our Planet and Journey into Space,” was four times the size of Greater London. There, Korolev worked his magic, building a series of rockets over several years.

The CIA reported, accurately, to President Dwight Eisenhower that thanks to Korolev’s powerful fleet of intercontinental missiles, the Soviets would be ready to put a satellite into space by 1958.

The Soviets were ahead of schedule by three months. And with Sputnik, as Tom Wolfe wrote in his frenetic classic of the space race, “The Right Stuff,” “a colossal panic was underway, with congressmen and newspapermen leading a huge pack that was baying at the sky where the hundred-pound Soviet satellite kept beeping around the world. … Nothing less than control of the heavens was at stake.”

Emboldened by the success of Sputnik, Korolev asked Khrushchev for permission to send “biological materials” into space. He had a long history of lofting dogs into the sky on massive rockets that had an unfortunate tendency to explode on liftoff. But in August 1960, one of Korolev’s new generation of rockets lifted off with two dogs, 40 mice, a rabbit, a pair of rats, and a bottle full of fruit flies – and this menagerie orbited Earth 18 times. All returned alive, after which Korolev extended his “biological materials” to include humans.

He began screening Soviet military pilots, thousands of them. The American astronauts in the competing Mercury program may have joked about being “Spam in a can,” but it seems clear that Korolev wanted to have plenty of cosmonauts on hand in case another rocket blew up.

One of the cosmonauts was a former fighter pilot named Pavel Romanovich Popovich, a good-humored man who quickly made his way to the top of the class. He was a likely choice to travel on the first manned launch, but, as Walker noted, he was handicapped by being Ukrainian. For even in the supposedly internationalist and multiethnic Soviet Union, the Politburo made clear to Korolev that a Russian had to go up first. (Popovich would have his turn aboard Vostok 4 in August 1962.)

Enter Yuri Gagarin, who ticked all the boxes: He was the son of a carpenter who grew up on a collective farm and had survived the Nazi occupation — though, it would emerge, he was traumatized by the experience, which included the attempted execution of his 5-year-old brother.

Gagarin had gone to trade school, earning top marks, before joining the Soviet Air Force and undergoing pilot training. He excelled as an aviator, and while, as Walker recounted, the head of the Vostok training program exclaimed, “All six cosmonauts are terrific guys,” Gagarin led the field from the moment he arrived for training. It helped, of course, that he was Russian.

So it was that on April 12, 1961, Vostok 1 lifted Yuri Gagarin into space, the first human being to travel there. His orbit, which lasted for an hour and 48 minutes, had a few unsettling moments. He lost radio contact with Earth for 23 minutes, during which time, Walker recorded, he amused himself by watching droplets of water float about in the cabin, released from his drinking tube.

Subscribe to CNN’s Wonder Theory newsletter: Sign up and explore the universe with weekly news on fascinating discoveries, scientific advancements and more.

He also had only the vaguest idea of where he was when he came back to Earth, at one point crossing over a corner of Antarctica before finally parachuting out over a collective farm like the one of his childhood. “Boys, let’s be acquainted,” he told the astonished farmers he encountered. “I am the first spaceman in the world, Yuri Alekseyevich Gagarin.”

Khrushchev crowed about the Soviet victory over his capitalist rival. Gagarin was feted, celebrated and put up in the finest hotels the country could offer. Lonely amid all the hubbub, he drank heavily and unhappily. Finally allowed to return to active service after spending time as a delegate to the Supreme Soviet, he died in 1968 in what authorities described as a “routine training flight.”

Four months after Gagarin’s spaceflight on Vostok 1, cosmonaut Gherman Titov circled Earth 17 times on Vostok 2. It would be another six months before American astronaut John Glenn joined the extraterrestrial elite aboard Friendship 7.

Meanwhile, a frustrated John Kennedy, realizing that the United States would have to find another event in the space race in which to compete, sent a memo to his vice president, Lyndon Johnson, asking, “Do we have a chance of beating the Soviets by putting a laboratory in space, or by a trip around the moon, or by a rocket to go to the moon and back with a man?”

Johnson conferred with NASA, returning with a projected price tag of $20 billion. Kennedy reversed an earlier round of budget-cutting, first extracting NASA’s assurance that an American would be on the Moon by 1970. Kennedy then addressed the nation, saying, “We go into space because whatever mankind must undertake, free men must fully share. … No single space project in this period will be more impressive to mankind, or more important for the long-range exploration of space; and none will be so difficult or expensive to accomplish.”

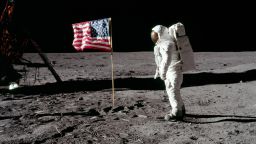

All of that turned out to be true, all the more so when NASA beat Kennedy’s schedule by 164 days and, on July 20, 1969, astronaut Neil Armstrong, accompanied by Edwin “Buzz” Aldrin, piloted the Apollo 11 lunar module Eagle to the surface of the Moon.

If only for his part in spurring on the space race 60 years ago, Yuri Gagarin deserves some credit for that transformative moment, too.

Gregory McNamee writes about books, science, food, geography and many other topics from his home in Arizona.