Ninety-year-old William Shatner, who gained fame portraying Captain Kirk on the original “Star Trek,” just hitched a ride aboard a suborbital spacecraft that grazed the edge of outer space before parachuting to a landing, making Shatner the oldest person ever to travel to space.

“That was unlike anything they described,” Shatner could be heard saying on the flight livestream just before landing.

Shatner blasted off onboard a New Shepard spacecraft — the one developed by Jeff Bezos’ rocket company, Blue Origin, and the same vehicle that took Bezos himself to space this summer. Bezos, a lifelong “Star Trek” fan, flew Shatner as a comped guest. With him were three crewmates: Chris Boshuizen, a co-founder of satellite company Planet Labs, and software executive Glen de Vries, who’re both paying customers, and Audrey Powers, Blue Origin’s vice president of mission and flight operations.

“What you have given me is the most profound experience, I am so filled with emotion, just extraordinary,” a visibly overcome Shatner told Bezos, immediately after emerging from the capsule. “I hope I never recover from this. I hope that I can maintain what I feel now.”

Their trip did not go exactly as the interplanetary jaunts Shatner captained during his acting career. New Shepard’s flight lasted just ten minutes from takeoff to landing, and gave the passengers about three minutes of weightlessness.

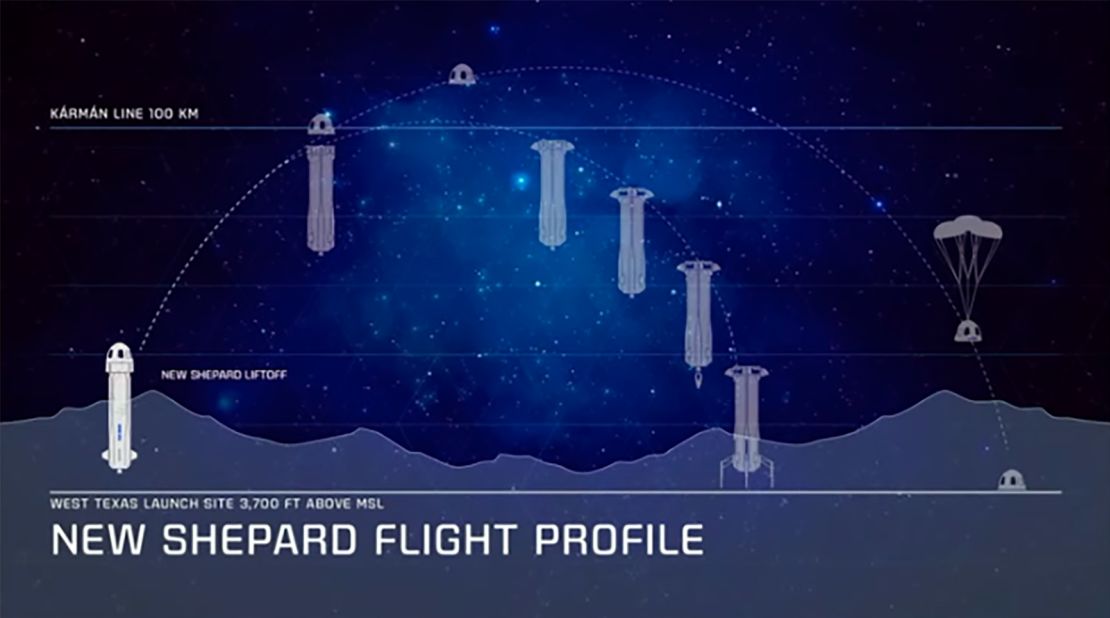

The group strapped into a capsule that sits atop the 60-foot-tall New Shepard rocket Wednesday morning after a series of wind-related delays. At 9:51 am central time, the rocket fired up its engines and roared past the speed of sound, vaulting the capsule up past the Karman Line, which, at 62 miles high, is one line used to demarcate the beginning of outer space.

Shatner and his fellow passengers were expected to experience up to 5.5 Gs — which feels like five times their body weight pressing onto their chests — during their 2,000-plus mile-per-hour journey. Upon descent, a plume of parachutes then fanned out above the capsule to slow its descent, taking it from more than 200 miles per hour to less than 20 in just a few minutes.

Shanter’s new record as the oldest person to fly to space one-ups the record set just three months ago by 82-year-old Wally Funk, who was a former astronaut trainee but was previously denied the opportunity to fly before she joined Bezos on his July flight.

Shatner’s flight marked the second of what Blue Origin hopes will be many space tourism launches, carrying wealthy customers and thrill seekers to the edge of space. It could be a line of business that helps to fund Blue Origin’s other, more ambitious space projects, which include developing a 300-foot-tall rocket powerful enough to blast satellites into orbit and a lunar lander.

But Shatner’s flight comes amid a wave of headlines that paint a picture of internal turmoil at Blue Origin, including several exits from the among senior-level staff in the wake of the company losing a key NASA contract to Elon Musk’s SpaceX.

A group of 21 current and former employees also co-signed an essay alleging that Blue Origin has a “dehumanizing” workplace environment that’s rife with sexism. It also claimed that the company has created an unsafe environment and many of the essay’s authors “say they would not fly on a Blue Origin vehicle.” Much of the current criticism also centers on the leadership style of Blue Origin’s CEO Bob Smith, who Bezos installed to run the company’s day-to-day operations in 2017.

Blue Origin did not respond to requests for comment about the safety allegations. But the company has repeatedly stated that safety is its top priority.

Powers, the Blue Origin vice president who will be flying on Wednesday, also responded to the safety allegations in an interview with CNN’s Erica Hill on Monday, saying the reports did not give her pause.

“I’ve been working at Blue on the new Shepard program specifically for the past eight years,” she said. “A team of very, very talented professionals and colleagues — some of the best that I’ve worked with in my 20 years in human spaceflight — have been committed to to the safe operation of this program.”

Is it safe?

Blue Origin has conducted more than a dozen uncrewed test flights of New Shepard, and Bezos decided to put himself on the first-ever crewed flight in July, in part to demonstrate that he trusts his own life with Blue Origin’s technology.

Blue Origin has billed New Shepard as a spacecraft that virtually anyone can fly on with only a few days of light training. Though the vehicle will put the passengers through intense G-forces as it blasts upward and returns back toward Earth, the ride won’t be nearly as intense as orbital flights like the one that SpaceX recently operated for four space tourists, which requires far faster speeds and a nail-biting reentry process.

(Read more about suborbital vs. orbital flights and the somewhat arbitrary attempts at defining where “outer space” begins here.)

On Blue Origin’s website, it states the following criteria for passengers:

- You must be 18 years of age or older.

- You must be between 5’0” and 6’4” in height and between 110 pounds and 223 pounds in weight.

- You must be in good enough physical shape to climb seven flights of stairs in a minute and a half

- You must be able to fasten and unfasten a seat harness in less than 15 seconds, spend up to an hour and a half strapped into the capsule with the hatch closed and withstand up to 5.5G in force during descent.

Still, spaceflight is inherently risky. Drumming up enough speed and power to defy gravity requires rockets to use powerful, controlled explosions and complex technology that always involves some uncertainties.

“I’m really quite apprehensive,” Shatner told CNN’s Anderson Cooper last week. “There’s an element of chance here.”

From a physiological perspective, however, Shatner’s age shouldn’t be an issue, according to Dorit Donoviel, the executive director of the Translational Research Institute for Space Health (TRISH), a Baylor College of Medicine-led research group that partners with NASA.

Donoviel pointed to a series of studies in which people with pre-existing medical conditions, including elderly men with heart conditions, who experienced up to 6Gs in a spinning centrifuge to simulate the crushing forces the body is put through during spaceflight.

“They were perfectly fine,” Donoviel said. “The only thing — medical condition — that was of concern when they did those studies was really anxiety and definitely claustrophobia.”

Blue Origin passengers could experience up to 5.5Gs, which can also make it difficult to breathe or move their hands and arms. But they won’t have the stress of piloting New Shepard, which is fully autonomous, so they can basically just sit there and wait out the most stressful portions of the journey.

One thing that is absolutely crucial for them, however, is to get back in their seats as soon as mission control warns the passengers that the capsule’s three minutes of weightlessness are about to be over. As the spacecraft begins falling back to Earth, and the crushing g-forces return, passengers who aren’t strapped into their seat and oriented in the proper position could risk serious injury.

“If they’re facing the [wrong] way, the g-forces could pull all the blood away from the head and go down to the feet, in which case the person would pass out,” Donoviel said.

This spaceflight also comes as Blue Origin is facing backlash from a group of 21 current and former employees — including senior engineers and managers who have worked across a variety of departments and programs — who co-signed an essay alleging that the company has a grueling workplace culture that makes it impossible for the New Shepard rocket’s engineers to guarantee its safety. The essay states that many of its signatories “say they would not fly on a Blue Origin vehicle.”

That news also came amid a flurry of headlines that paint a picture of internal turmoil at Blue Origin, including a wave of exits among senior-level staff.

Blue Origin did not respond to requests for comment about the safety allegations. But the company has repeatedly stated that safety is its top priority.

Powers, the Blue Origin vice president who will be flying on Wednesday, also responded to the safety allegations in an interview with CNN’s Erica Hill on Monday, saying the reports did not give her pause.

“I’ve been working at Blue on the new Shepard program specifically for the past eight years,” she said. “A team of very, very talented professionals and colleagues — some of the best that I’ve worked with in my 20 years in human spaceflight — have been committed to the safe operation of this program.”

What happened?

When most people think about spaceflight, they think about an astronaut circling the Earth, floating in space, for at least a few days.

That is not what the New Shepard passengers did. In fact, it looked very similar to Bezos’ flight back in July.

They went right up and came right back down, and they did it in less time, about 10 minutes, than it takes most people to get to work.

New Shepard’s suborbital fights hit about three times the speed of sound — roughly 2,300 miles per hour — and fly directly upward until the rocket expends most of its fuel. The crew capsule then separated from the rocket at the top of the trajectory and briefly continued upward before the capsule almost hovered at the top of its flight path, giving the passengers a few minutes of weightlessness. It works sort of like an extended version of the weightlessness you experience when you reach the peak of a roller coaster hill, just before gravity brings your cart — or, in this case, your space capsule — screaming back down toward the ground.

The rocket, flying separately after having detached from the human-carrying capsule, re-ignited its engines and used its on-board computers to execute a pinpoint, upright landing.

What’s the point of all this?

Blue Origin plans to use New Shepard to compete directly with British billionaire Richard Branson and his suborbital space tourism company, Virgin Galactic.

Virgin Galactic’s tickets cost about $450,000 — more than the median home sales price in the United States. Blue Origin has not publicly set a ticket price, though it did recently sell one at auction for a whopping $28 million. Shatner will be flying as a complementary guest, though Bezos said in July that the company has sold nearly $100 million worth of tickets in total.

This is all part of a much broader push by commercial space companies — and NASA — to make space a place of business. The idea is that the private sector can spur innovation and drive down costs, paving the way for a future in which everday people — not just professional astronauts — live and work in space. That vision has elicited plenty of criticism, with skeptics questioning whether we can build an equitable future in space if it’s mapped only by those with means.

It’s also not clear how much sustained interest suborbital space tourism will garner from the world’s wealthiest people. But Blue Origin and Virgin Galactic also plan to parlay their technologies into other ventures. In Blue Origin’s case, that includes building a massive orbital rocket for launching military, science and commercial satellites and a lunar lander. Though, Blue Origin’s bid to make a vehicle that will land the next humans on the moon was recently turned down by NASA and is now caught up in a court battle.