On its face, the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences’ apology to Sacheen Littlefeather earlier this year appeared to be a long overdue righting of wrongs.

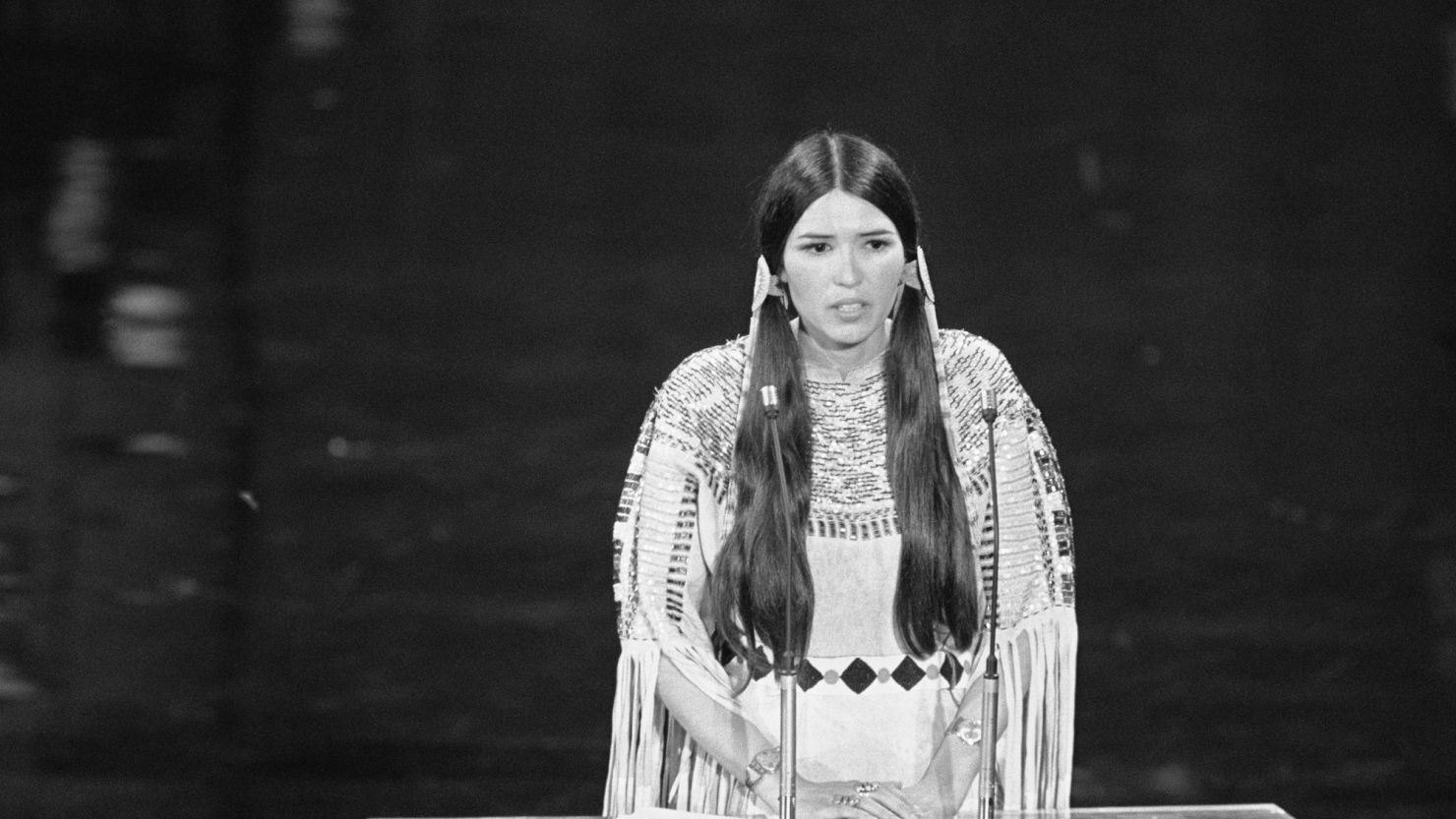

The actress and activist famously declined the best actor Oscar on Marlon Brando’s behalf at the 1973 Academy Awards. In her 60-second speech, she introduced herself as Apache and spoke out against Hollywood’s treatment of Native Americans. Over the years, she became an icon, saying in interviews that she was White Mountain Apache and Yaqui, that she participated occupation of Alcatraz and that she was blacklisted by the film industry.

Two weeks after her appearance at the Academy Museum’s formal apology event, Littlefeather died. And soon afterward, writer Jacqueline Keeler called her entire legacy into question.

Citing a review of Littlefeather’s family tree, interviews with her two sisters, and consultations with tribal leaders, Keeler alleged in an op-ed for the San Francisco Chronicle that Littlefeather wasn’t who she had claimed to be. Keeler concluded that while Littlefeather possibly had Indigenous ancestry, she wasn’t connected to the White Mountain Apache or Pascua Yaqui tribes. (CNN has reached out to both tribes for comment and has been unable to independently verify whether any of Littlefeather’s ancestors were enrolled in either tribe.)

In other words, Keeler wrote, Littlefeather was a fraud – a “Pretendian” who built a career and livelihood around a false identity.

Keeler’s op-ed set off a wave of heated debate among Native Americans. Some said that the report confirmed what they and many others in Indian Country had suspected all along. Others cast doubt on Keeler’s methods and accused her of gatekeeping: Who was she to determine who counted as Native and who didn’t? And why were Littlefeather’s sisters coming forward now after her death?

But at the heart of the Littlefeather controversy is a more fundamental question, Native American scholars say, about what it means to be Native American.

Genetic ancestry isn’t enough

You’ve probably heard someone say they’re “part Cherokee.”

People often claim that they have “Native blood” in casual conversation or check the “American Indian/Alaska Native” box on application forms without being able to point to a direct Native ancestor in their family tree. While some of those people are exaggerating or lying for economic or professional opportunities, plenty of them genuinely believe that they are Native American, said Kim TallBear, a professor of Native Studies at the University of Alberta.

That stems partly from a deep misunderstanding of what it means to be Native, TallBear said. Many people base their claims on family lore or the results of direct-to-consumer genetic ancestry tests. But having a long-lost ancestor or “Native American DNA” isn’t enough to claim affiliation with a particular tribe, she added.

“It hinges on family, and that doesn’t mean an ancestor or a purported ancestor five to 20 generations ago,” TallBear, who is a citizen of the Sisseton Wahpeton Oyate, said. “That means people you actually know or can get to know, that aren’t just bones in the ground from a long time ago.”

Being Native American is often viewed in the US as a race or ethnicity. The number of people who identified as American Indian and Alaska Native alone and in combination with another race in the 2020 Census was 9.7 million, up from 5.2 million in 2010 – Circe Sturm, an anthropology professor at the University of Texas, Austin, has theorized that at least part of that jump can be explained by people claiming a distant ancestor or the results of a genetic ancestry test.

TallBear and others say this view misconstrues how tribal governments and communities function. Tribal nations are political entities that set their own terms for belonging, generally emphasizing kinship and engagement with the community. She contests the notion that a person can merely self-identify as part of a tribe – as the Academy Museum suggested in response to the allegations about Littlefeather.

“Native American and Indigenous identity is deeply complex and layered, especially in the United States, and these communities have long battled erasure and misrepresentation,” the Academy Museum said in a statement to CNN. “With the support of its Indigenous Alliance — an Academy member affinity group — the Academy recognizes self-identification.”

TallBear avoids the term “identity” when talking about tribal affiliation and citizenship. It’s too individualistic, she said, and not reflective of Indigenous values.

“We’re seeing a major tension in worldviews between Indigenous collective ideas of what it is to belong to the people versus settler ideas of individual identity rights and claims,” she said.

Littlefeather’s sister Rosalind Cruz, who was estranged from the late actress, told CNN that her family didn’t consider themselves Native when she was growing up. Later, Cruz assumed she was eligible for citizenship in the White Mountain Apache Tribe based on her sister’s public statements, but said she was told by tribal officials that there were no records of anyone in her family being enrolled in the tribe.

Even before Keeler’s op-ed, a statement on Littlefeather’s website characterized the doubts about her heritage as misinformation, and stated that her father was “from the White Mountain Apache and Yaqui tribes from Arizona.”

Tribal belonging is a complex issue

Tribal citizenship and belonging, however, are complicated. There are some who feel that Keeler’s report on Littlefeather and her investigations into other alleged “Pretendians” are discouraging for people who are trying to reconnect with tribal communities they have been severed from.

Chris La Tray, a Métis writer and storyteller, has been there. Growing up in Missoula, Montana, he said his father and grandfather always denied any Native heritage, though his grandmother would say they were Chippewa. La Tray claimed that identity for himself even though he wasn’t raised in a tribal community. Upon researching his family tree, he found that he was indeed connected to the Little Shell Tribe of Chippewa Indians of Montana – a tribe that was historically without a reservation and only received federal recognition in 2019.

La Tray is now an enrolled member of the Little Shell tribe, but he said he’s more interested in welcoming others like him back to their communities than he is in disputing people’s claims to Native identity.

“You have people who think that the only way that you can be considered an Indigenous person is if you grow up culturally within your tribe,” he said. “That is impossible for many of us.”

There are various reasons that someone with a legitimate link to a tribe might not be enrolled, many of which can be traced back to US policies that sought to erase Native Americans. Their families may have been forced to assimilate through federal boarding schools or the urban relocation campaign, or they may have been adopted into White families. Others might not qualify under controversial blood quantum standards, which require a certain amount of “Indian blood” and are a product of US colonialism.

There’s a clear distinction between people like La Tray and those who are claiming a tribal affiliation with little to no basis, TallBear said. For one, there are specific relatives or tribal community members that they can connect with.

Keeler said she and tribal officials have been unable to pinpoint a specific White Mountain Apache or Yaqui ancestor of Littlefeather’s based on enrollment records and genealogical research. The Pascua Yaqui Tribe of Arizona told The New York Times that neither Littlefeather nor her parents were enrolled in the tribe, but “that does not mean that we could independently confirm that she is not of Yaqui ancestry generally, from Mexico or the Southwestern United States.”

Of her efforts to identify “Pretendians,” Keeler told CNN, “This is not about people who are genuinely trying to reconnect with Native relatives. This is about people who have built their careers on claims to Native identity and who do not have any.”

The problem is especially prevalent in academia – just this week, a University of California Berkeley professor walked back her claims that she was a descendant of the Mohawk and Mi’kmaq Nations.

Keeler said she is committed to exposing people who falsely claim to be Native because they cause harm to tribal communities. They take jobs and opportunities from actual Native people, and speak for them when they don’t have a material stake in policies and legal battles that affect Native Americans. Still, others don’t always realize the extent of the damage.

In fact, Cruz said her family didn’t previously raise concerns about Littlefeather’s claims because they assumed she “wasn’t hurting anybody.”

In La Tray’s view, assessments about whether Littlefeather or anyone else has a legitimate claim to being Native should be at the discretion of tribes. After all, before Europeans arrived on the continent, many tribes were more inclusive in their membership, granting citizenship to people who married into or were adopted by the tribe, outsiders who lived in tribal communities and those who assumed their cultural norms and practices. Some tribes still adhere to more open criteria.

For all of their complications, tribal citizenship rules are continually evolving. Tribal nations are still grappling with the ramifications of colonialism and are constantly adjusting their enrollment criteria to reflect demographic changes and other shifts, TallBear said.

But Littlefeather’s case isn’t about blood quantum or other factors that keep some Native people from being a part of their communities, she added. It’s about what gives someone a claim to tribal belonging. So far, she hasn’t seen any credible proof.